Trip to India

December, 2006

Glenn Story

Copyright © 2006, 2007, 2008 Glenn Story

All Rights Reserved

Trip to India

December, 2006

Glenn Story

Copyright © 2006, 2007, 2008 Glenn Story

All Rights Reserved

Saturday, December 2: Delhi to Mandawa

Sunday, December 3: Mandawa to Jaipur

Monday, December 4: Ajmer and Pushkar

Wednesday, December 6: Jaipur to Agra

Sunday, December 10: The Wedding Ceremony

Monday, December 11: Agra to Delhi

NOTE: This is an online edition of

this journal. There is a printable version (some 256 pages) that contains more

photos.

It is now 10 a.m. I'm sitting in the boarding area for the

Singapore Airlines flight to Seoul, Korea and then to Singapore. After a day's layover in Singapore we will proceed to Delhi for the start of a

two-week's stay in India. India! I've always wanted to visit this place—home of one

of the world's oldest and still flourishing civilizations. And I'm going under

the best possible circumstances: my wife and I have been invited to the

wedding of my friend, Ruchi. I first met Ruchi at a company-sponsored technical

conference in Minneapolis. She volunteered (with a little prodding from me) to

collaborate on keeping some lab computers running—computers used by people both

in Mountain View (where I work) and also Pune, India (where Ruchi works.) After the conference, Ruchi visited Mountain View and it was

there that I told her that I hope to one day visit India. She promised to show

me around if I could only convince my management to send me on a business trip. Once Ruchi returned to Pune, we began a sporadic email

exchange, mostly about business at first, but gradually including personal

topics as well. Email soon gave way to IM (Instant Messaging) when she figured

out my IM address. It was during this period that I broached the subject of the

Indian custom of arranged marriage. Not long after that she excitedly informed me that her

parents had arranged for her to marry. It was soon thereafter that that she

invited me to attend the wedding. The practice of arranged marriages seems quite foreign to

most Americans, but I told her that my wife's parents (who are Chinese) had an

arranged marriage and it is clear to me that those two have a successful,

loving marriage. I hope and believe that Ruchi will have the same. But what

about being in love? Is she missing out on what I consider one of life's great

joys? Or is it possible to experience that joy within the context of an

arranged marriage? I think (hope for her) that it is possible. But now she is far too busy to consider such questions.

Preparing for the wedding—Hindu weddings are far more elaborate than those in

the west—is occupying virtually all of her time. It is an exciting time in her life and I am grateful that

she is sharing it with me. I'm grateful also to Ruchi’s parents—whom I have

yet to meet—for inviting my wife and me into their home. This no doubt adds to

the work and stress on their part in preparing for the wedding. At this point

it is not clear whether, as foreigners, we will be treated as guests of honor,

or whether we will be lost in the crowd. For a crowd there will be. There are

over 900 people expected at the wedding. Ruchi is a Hindu, so this will be a Hindu wedding. I know

little about Hindu weddings, but Ruchi has arranged to have her “cousin” explain

the ceremony. (I put “cousin” in quotes because I have found that Ruchi, like

most Indians, applies this word—as well as “aunt” and “uncle” to close friends

as well as true relatives.) I also know little about Hinduism as a religion. I've

brought a book along on the subject to help occupy the time waiting for and

during the flight. I have already read enough to know that it is a very

complex religion. I have come to realize that there are three (at least)

aspects to understanding a religion: (1) theology or what the religion teaches;

(2) religious practice—both group and individual. This includes both moral

practice and religious ritual. Finally, there are individual beliefs. One

would think this is the same as the religious teachings, but my experience is

that it is not. Individual beliefs vary, obviously, with the individual, but

they tend to be simplified compared to the “official” theology, and in some

cases actually contradict the latter. The book I have will no doubt concentrate on the first

aspect—theology. I hope to learn more about the latter aspects while in India and particularly while staying with Ruchi’s family. The cabin crew has just arrived. The stewardesses are

gorgeous! They are wearing floor-length form-fitting dresses with colorful,

complex geometric patterns. They hearken to a day when stewardesses were all

young, pretty, women—a practice no longer legal or politically correct in the U.S. Next the flight crew arrives, all men, wearing

quasi-military uniforms with hats and piping on their sleeves. Our lives will

be in their hands for the 13 hours from here to our first stop--Seoul, Korea. When we arrived at the boarding area we were the only ones

here. Now, 15 minutes before scheduled boarding there are about 100 people—that's

pretty much the full complement, I'm told, for the flight to Seoul. I'm also

told the flight is overbooked from Seoul to Singapore. I guess the mix of people is somewhat representative of the

people of Singapore—a mixture of east Asians (Chinese, Koreans) and south

Asians (Indians), and a few round-eyes like me. There is a young Indian woman holding a baby. There is an

old man bundled as if prepared for a snow storm. Now we are on the plane. The flight path takes us up the

west coast of the U.S. and Canada, across Alaska and the Bering Straits, then down over Siberia. It's been some years since I've been on an international

flight. The aircraft is much the same as those I've flown in the past, but the

entertainment system is much more advanced. There is a video screen in each

seatback with dozens of channels of on-demand movies, TV shows, and music.

Right now I'm listening to Indian pop music. The current song is “I’m Ready,

Ready, Ready for Love.” (The chorus is in English, but the verses are in

Hindi.) This song is likely from a “Bollywood” movie. It makes me think again

of romantic vs. arranged marriages. I know that Ruchi loves these love songs

and movies. Yet she's agreed to an arranged marriage. In fairness, the movies

(if not the love songs) extol the traditional values—typically the girl

forsakes the young man she's in love with to follow her parents’ wishes and marry

the one her parents have chosen for her once she realizes that this is the path

to real love and happiness.Departure

Tuesday, November 28,

2006

We arrived in Singapore late last night. With very little trouble we cleared immigration & customs and found the airlines-provided shuttle to the hotel.

Today we spent the day sight-seeing in Singapore.

First we took the subway to Chinatown. It reminded me of Chinatown in San Francisco: Chinese-style tile-roofed buildings with the ends upturned, red paper lanterns. But other things were different. There were more Chinese herbal medicine shops than in San Francisco. More vivid smells of exotic foods, and other less-easily-recognized aromas, and most surprising of all: a large Hindu temple which we learned was the oldest in Singapore.

This co-existence of diverse ethnic and religious groups not only in the same country, but literally side by side, was refreshing and encouraging.

From Chinatown we took a shuttle bus by a very indirect route to the part of town called “Little India.” We knew the route would be indirect: it gave us a chance to see more of the city.

What we saw was very impressive: First and foremost: the obvious prosperity here. We drove past large colonial-era mansions, an elligent shopping area reminiscent of Ginza in Japan, complete with Japanese department stores such as Takashimaya as well as American stores such as Gap and European stores like Emporio Armani.

We saw wide, well-maintained avenues with lots of cars but no serious congestion.

And construction. Everywhere, construction. It is clear that the economy is thriving and growing. Singapore is the only country in the 20th Century, to my knowledge, to make the transition from “developing” to “developed.”

There were two things that surprised me—both pleasant surprises. First, the amount of greenery. True, Singapore is in the tropics, located on an island that was once jungle, but I had expected that would have all been replaced by concrete, chrome and glass. Of course, there is plenty of the latter but streets are lined with trees and flowers and there are frequent parks and open space. This city was designed to be both an efficient and a pleasant place to live and work.

The second surprise was how colorfully painted the buildings were. Of course, one would expect religious buildings—particularly Hindu temples—to be colorfully decorated with depictions of Krishna, Shiva, and others of the myriad of Hindu deities. But private dwellings as well were painted in a variety of bright colors—even the government-built high-rise housing projects had vivid yet tasteful colors. For example, one such building (which would have been left as unpainted gray concrete in an America city) was bright white except for the top two floors which were a solid forest green. So Singapore was literally colorful as well as exciting.

Singapore has been a kind of transition for us: clearly Asian but still familiar in many ways: a modern city with the sights one would expect in any large city from the U.S. or Europe.

Now we are on our way to our real destination: India.

A magazine on the plane has the cover story, “The New Laws of Marriage [in India]. Increasing legal intervention changes the dynamics of India marriage and social tradition.” The changes to me seem all for the best, giving women—women like Ruchi—more freedom and equality than tradition had allowed. I don’t mean this to be a put-down of Indian tradition. God knows our own Judeo-Christian tradition has its problems with the role of women. And I'm all for the preservation of tradition. Indian culture, like many others, is at risk of being melded into the world culture which is largely American.

It is Friday morning. Our arrival in Delhi was more or less uneventful. Immigration was speedy and efficient. The uniformed agent stamped my passport, handed me a card to give to customs, and off I went to baggage claim.

Baggage claim was much like that in any airport: baggage carousels, carts, and people crowding about and looking for their bags. There was a young Indian girl, perhaps three years old who made her way fearlessly through the forest of adults to get a front-row view of the bags coming by. She was oblivious to the dozens of people manhandling large heavy bags around her. Her mother held back some distance but seemed unconcerned about her daughter's peril. It was only when a suitcase came close to whacking the child, and I held out my arm to protect her that the mother took note and called the child back.

Customs consisted of handing my form to a customs agent and being waved through.

We passed through a set of doors and into another room. There was a crowd of people holding signs with people's names. There must have been a hundred of them and a like number without signs—presumably family members or friends of arriving travelers.

We expected our driver to be among the sign holders. My wife and I agreed that she would look on one side and I on the other. We walked some distance before she spotted a sign saying, “Mr. Glenn”. Was this a confusion of my surname/given name, or a difference in custom? Or was the sign for someone else? We made eye contact and I approached him. We exchanged introductions. It was indeed our driver, Mr. Singh. With a name of “Singh” I had expected a Sikh, who would have worn a beard and turban. Instead Mr. Singh was clean shaven and without head cover.

He led us out from the crowds—which were less than I had feared—into the parking lot. There was a bigger crowd outside the terminal, offering taxi rides and help with our bags.

In the parking lot itself cars were diagonally parked but then there were cars parallel parked in front, blocking the former's exit. Mr. Singh's car was diagonally parked and like all the others was blocked by a parallel-parked car. How would we get out? The solution was simple. All the parallel parkers left their cars in neutral with the parking brake off. We simply pushed a few cars out of the way and made our escape.

A group of young men came forward to help us putting our bags into the car. I tipped them way too much, and Mr. Singh gave me a stern lecture.

Traffic out of the airport was heavy but moving steadily. Drivers tended to ignore lane markings and made liberal use of their horns.

I tried to look out the window to get my first view of India but it was surprisingly dark. I could see people—lots of people—walking along the roadway, but little detail beyond that. It seemed like we were going past an endless stream of small shops, the purpose of which was, for the most part, inscrutable.

It took about half an hour to get from the airport to our hotel. Along the way, towards the end, the driver stopped several times to ask directions to the hotel.

The hotel is small and not very brightly lit from the outside. A bellboy took our bags. We discussed with our driver how and when to meet the following day.

Inside, we were directed to the first floor. This seemed to confuse my wife. I realized that we were on the ground floor and that they were using the British system where the first floor is above the ground floor, rather than the American system where the ground floor is the first floor. In this case the British system made particular sense because the ground floor was taken by shops, and the hotel only began above that on the first floor.

At the front desk I presented our voucher and passports and filled out a registration form and a registry entry.

The room we were taken to had not been cleaned and the bed was not made. So the bellboy went back to confer with the desk clerk and we were assigned to a different room. It was neither luxurious nor dingy, but came closer to the latter. There was an overpowering odor of naphthalene. I opened the window to reduce the smell, only to be regaled to the aroma of wood smoke. The view out the window was across a small courtyard to a similar sized building, made of concrete which has needed a paint job and repair work for at least 25 years. In our room there is a double bed. The bathroom has a western style toilet and a shower.

Shortly after our arrival, Ruchi called as previously planned. She seemed worried when I told her that our driver's English was minimal, but I'm not concerned—I’ve traveled and lived in Japan where English understanding is largely absent entirely. I've learned to speak slowly, listen carefully, and accept that comprehension on both sides will be less than 100%.

We finally got to bed by 2 am and awoke by 5—jet lag plus the fact that I, for one, slept almost the entire trip from Singapore.

We took the time to repack our bags and I have been updating my journal.

Breakfast was a buffet—mostly Indian foods. There was a potato dish, some others that I couldn’t identify. Each had a different color and appearance, and different flavor. All were delicious. There was also porridge, and corn flakes. The cleanliness of the plates was variable but the taste was great.

After breakfast I wanted to walk down the street to a Nokia store I had seen from the car the night before. I knew it wouldn’t be open this early but I wanted to see if they had posted hours. Besides, I wanted to explore. Ruchi would have disapproved, but it was only a short, straight walk. We didn’t even need to cross any streets.

The store was, as expected, closed. No hours were posted—the store was shuttered.

On the way back to the hotel we were greeted by some guy who struck up a conversation. His English was excellent. He offered to take us to a government tourist agency where we could get maps. He also offered to take us to an “emporium.”

“No money,” he repeated several times, “only to help you. If I come to your country you can help me.” I doubted that would come to pass but I appreciated the sentiment. We agreed to walk with him.

As we walked along the busy, dusty streets he told me he is a yoga teacher. The street was crowded with foot, bicycle, and motor traffic. In the U.S. the motorcycle drivers tend to be rule breakers, whereas the car drivers more-or-less follow the rules. Here the opposite seems to be the case: the motorcyclists are the more conservative—which actually makes more sense since they’re more at risk from an accident than a car driver. There are certainly more motorcycles—or rather motor scooters—than in the U.S. Even Ruchi drives one.

When we reached the travel agency, we thanked our guide and went in. The man we spoke to encouraged us to buy presents and souvenirs in Delhi rather than Jaipur. The Delhi merchants, he explained, are more honest than those in Jaipur. Perhaps his income derives at least in part from making that kind of assertion.

When we left the travel agency, the man who had guided us was still around. Next, he took us to the previously mentioned “emporium.” Now his true motivation became clear—I saw the man at the door pass him a “commission” for leading us to this shop. The shop itself was very elegant and displayed costly jewelry and other expensive wares. We spent less than a minute and left. We then returned to our hotel.

Once our driver arrived, we walked around to the back of the hotel where there was a small shop selling SIM chips for cell phones. I bought one for a phone I had carried from the U.S. (I had previously had the phone “unlocked” in the U.S.) The process of getting the SIM chip was amazingly bureaucratic. I had to give them a passport photo (supplied by another shop close by) and a photocopy of my passport, which the phone shop provided. I also had to fill out an intricate form. I have read—and previous experience in choosing a travel agency confirmed—that Indian businesses have a fondness for forms and bureaucracy, reserved in the U.S. to government agencies. This, no doubt, is a lingering curse left over from the British Raj (the term used for the period of British involvement in India). In any event, I was prepared for the complexity by the travel agent we had spoken to earlier this morning.

The travel agent had also told me that the cell phone would take four to six hours to activate, so it was actually a pleasant surprise when they said it would take 10-15 minutes. I had hoped it would activate immediately so that I could verify that it was working properly, but that's not how it works here.

So with soon-to-be-working cell phone in hand, we went to our next stop: a chemist (British for “drug store”). I had gotten a sore throat and cough the night before. I had brought all kinds of stomach medicine to India but hadn’t even considered bringing cold medicine. The chemist shop, like the cell-phone store was little more than a stall. The chemist spoke excellent English and when I told him my symptoms he produced a medicine to cure them. In India, they sell medicine by the pill; this medicine was two rupees per pill. I bought 10 and thus paid 20 rupees—the equivalent of about 50 cents.

Finally we were ready to start sight-seeing.

The first place we went was the area of Indian government buildings. We saw the Parliament Building, the Prime Minister's residence, and several large monuments laid out along a grassy mall reminiscent of the capital mall in Washington D.C. This entire area was area was lined with flags of India as well as flags of Jordan. The newspapers say that the King of Jordan is here on a state visit.

From there we traveled to the Humayun’s tomb where we encountered two setbacks. First, the admission cost, which our travel agency claimed was prepaid, had not been properly arranged. Second my cell phone, which activated, as evidenced by two text messages, plus my ability to make a call to confirm the activation, stopped working almost immediately thereafter.

While I was handling the cell phone activation and looking for our driver to straighten out the admission policy, a large number of children in school uniforms came pouring out of the monument and running past us. Many of the boys and four of the girls said “hello” to us. One small boy stopped and shook my hand. It was delightful.

Back at the car, the driver knew nothing about the admission prices so I tried using his cell phone (since mine wasn’t working) to call Nikunj, our travel agent (who is in Mumbai). I was given or wrote down an incorrect phone number because I got the tones of a fax machine. The driver took his phone back to hear for himself. He was going to try again when his phone rang. It was Ruchi. What fortuitous timing! She was wondering why I hadn’t called her with my cell phone number. I explained that it wasn’t working and also explained about the admission-price problem. She said she would call Nikunj and call us back. Meanwhile a park policeman was growing impatient with our illegally parked car. He rolled his eyes but said nothing when told we were waiting for a return call.

While we were waiting a man came along the street, sat down on the pavement, set a basket in front of him and produced a small wind instrument. I recognized its gourd shape and knew what to expect next. The man removed the lid of his basket and immediately a snake stuck its head out. It spread its hood confirming itself to be a cobra—one of the deadliest snakes on the planet. But then the snake charmer saw the policeman who was still hovering near our car. He put the lid on his basket, stood, and moved off.

A group of soldier came by. I was afraid they would be more forceful in getting us to leave but they said nothing.

I was getting hungry and we were clearly obstructing traffic so I told our driver to take us back to our hotel for lunch.

I love Indian food. There were plenty of both meat and vegetarian dishes on the menu. I have been advised to avoid meat while I'm in India. I had palak paneer—a mixture of creamed spinach and a mild Indian cheese. “Paneer” is sometimes translated as “cottage cheese” but its consistency is closer to that of regular cheese although it is not nearly as sharp in flavor as western cheese. My wife ordered a vegetable curry. She ordered rice and I ordered naan (Indian flat bread). The meal was quite good and not overpoweringly spicy as I had somewhat expected.

After lunch we returned to the SIM-chip shop. There they did exactly what I would have done: they switched my SIM chip to a different phone, where it worked correctly. So they sent me to the Nokia store that is on the same street as our hotel. There they redid the same swapping test and then tried to sell me the most expensive phone they had in stock. I bought the cheapest for 2200 rupees (roughly US$50). Now I have a strong signal and have made and received calls with Ruchi. (Ruchi is probably the only person I need to call while here, although I might call our driver or her family members if need be.)

When the British came to India they eventually decided to make a capital in Delhi, but modernizing that town seemed too difficult so they simply build a new town next to the old: New Delhi. It is in New Delhi that our hotel is located as well as the places we saw this morning.

This afternoon we headed to (old) Delhi. (Note that it is not called “Old Delhi.”)

On the way we stopped at the Raj Ghat which is a large tract of land containing the burial place and memorial for Mahatma Gandhi as well as other members of the Gandhi family.

The Mahatma's memorial is both simple and elegant. In the center is a flame surrounded by an expanse of grass with several paths leading from it.. To one side are a of perhaps 50 people sitting and spinning to memorialize the trade that Gandhi (a lawyer by training) adopted to show respect to that and all other simple trades. Surrounding this central area on all four sides is an elevated wall with a walkway on the top. This wall/walkway forms a square around the center court. In the middle of each side of the square is a tunnel allowing admittance to the central court and on each side of the tunnel is a ramp leading up to the elevated walkway.

The beauty and simplicity of this place seem fitting tribute to the man who championed the independence of India. Perhaps even more important is Gandhi's role in demonstrating to people everywhere—not just in India—the possibility of overcoming tyranny without resorting to violence. Gandhi's influence on Martin Luther King, Jr., is well known and so it is fitting for foreigners such as us to join the Indians who come to this place to pay Gandhi tribute.

At last we made our way into Delhi where the buildings are older and less European, the roads narrower and the crowds larger.

We came to the Jama Masjid. This is a Moslem mosque said to the greatest in India. Our driver let us out of the car, we climbed the stone steps to the south entrance gate. At the top we removed our shoes and my wife covered her head with a scarf. Then we stepped into the stone-floored courtyard. The main mosque building is along the west side, presumably so that worshipers can face—and be closer to—Mecca when they pray. There is a smaller building on the opposite wall and tall minaret towers.

Our original schedule called for us to see this mosque in the morning but I'm glad we came later. The late afternoon sun added to the beauty of the place.

We came out, recovered our shoes, and paid some boy 10 rupees for watching them. From the top of the steps I looked down on the mass of building and people below.

We returned to our car and drove back to our hotel. On the way we saw an elephant traveling the road in the opposite direction.

Once back at the hotel, I went to buy more minutes for my cell phone at Ruchi’s advise. Then we went to dinner. I had Paneer Thika—the same cheese I had for lunch but this time cooked in a tandoori oven.

During dinner we were entertained by a group of three musicians, one playing tabla (Indian drums), one playing a harmonium, (a hand-pumped organ, originally from Europe and no longer used there. It is widely used in India.) The third musician played a synthesizer. There was also a woman on the stage whose role was unclear. The harmonium player also sang.

After dinner we went back to our room and I took a shower. Shortly after I turned on the water, while I was still adjusting the temperature, the trap in the drain suddenly popped up and a 4-inch long centipede came scrambling out and began frantically running around the shower trying to escape the water. It frankly scared the bejesus out of me. I eventually captured it in a cup—I had no intention of sharing the shower with that creature.

Today we left Delhi to travel to Mandawa. The first part of our journey was through Delhi, retracing in part, the route we had taken from the airport. Then we got on something like a freeway—it was divided and had on-ramps and off-ramps. But, it also had access to roadside business—gas stations and small shops. Also, unlike an American freeway, there was some foot and bicycle traffic.

Eventually, the road became two lanes. This is when driving becomes interesting and I'm glad we had a local driver. The rules on when and how to pass are quite different from those in the U.S. At first it seemed like chaos but gradually a pattern emerged. Whereas in the U.S. passing is done at high speed and with no expectation of co-operation from other vehicles, here the speed is lower and other drivers—both those being overtaken and oncoming—co-operate by moving aside, motioning when to pass, etc. The driver honks to pass. This is not considered aggressive or rude as it is in the U.S. In fact many trucks have signs like “Please Honk.”

We drove through many small towns, the streets lined with fruit and vegetable stands and throngs of people, walking, some with large bundles on their heads, or just standing around. The women were all in saris of bright colors.

The further we got from Delhi, the more foot traffic we saw. We also increasingly had to share the road with carts driven by camels.

The road got noticeably more bumpy when we crossed into the state of Rajasthan, where we will spend most of our remaining sight-seeing time.

We passed through one area where there were tall (50 feet or more) cylinders that are the smokestacks for brick kilns. Bricks were piled everywhere.

It was just past this region where we stopped for lunch at the mediocre-sounding “Midpoint Motel.” But neither the food nor the location were mediocre. We ate outdoors in a large grassy courtyard. There was a buffet with several spicy vegetarian dishes and one chicken dish. I was tempted by the chicken but decided to stick to eating vegetarian foods while in India. When I say “spicy” I refer to the richness of flavor not to the hotness. (I know that both Spanish and Japanese have separate words to distinguish “hot spicy” from “hot temperature” and I understand Hindi does as well. In fact, the Japanese word for “hot spicy” is “curai-no-agi” which I would translate as “flavor of curry.” I am constantly reminded of India’s contributions to world culture—curry is, so far as I know, an Indian invention.) Anyway, it is this richness of flavor that makes it so easy—in fact enjoyable—to stick to my “no meat” rule.

After lunch we continued on our way. The road narrowed from two lanes to one. The amount of traffic was greatly reduced but when we did meet an oncoming vehicle one or the other of us had to move to the wider unpaved shoulder.

We reached Mandawa in late afternoon. We wound through narrow streets, many unpaved. We turned on a side road and there ahead of us was a large castle, apparently in ruin.

We drove through the front gate into a sand-covered courtyard. We could now see that while parts of the castle were indeed in ruin, there was one portion that has been restored and is actually in use. This is where we will be staying.

Two bell boys in spotless white uniforms and orange turbans came to take our bags. After checking in we were led through a series of narrow hallways and an inner courtyard to our room. The lock on the door is actually a padlock and the double door is held closed with a bolt rather than a latch.

Inside is a maze of short hallways and low doors leading to a large bedroom and equally large bathroom with a huge bathtub.

After we settled in, we rejoined our driver who turned us over to a guide who walked us around the town's narrow dirt streets showing us a mixture of old buildings in various states of disrepair and some old and new frescos on various buildings.

We came back to the Mandawa Castle and explored the grounds. There is a beautiful swimming pool, and the inner courtyard was being prepared for dinner.

Now I am sitting in a veranda adjacent to the registration desk, catching up on this journal. I am looking out on the outer courtyard. It is now dark and it is easy to distinguish the lit, occupied portion from the dark, older part. There is a cannon pointed to the main entrance.

Except for one automobile parked next to the stairs, it would be quite easy to imagine that I am in the 19th or even 18th century.

Suddenly a loud bell sounds—three groups of two, followed by a single ring. I guess it means it's seven p.m.

Dinner was served in the inner courtyard with tables around a wood fire. The meal was fixed menu, served by a staff wearing orange turbans with the end hanging loose down the back. (All the staff here wears this outfit.) The first course was an appetizer consisting of small portions of various Indian dishes. Next came cream of tomato soup with croutons, salad, which we declined for health reasons. (We’re not eating uncooked fruits or vegetables to protect our stomachs.) Then came the main course consisting of a mix of meats, some prepared in a more western way, and some in an Indian style. Dessert was two different fresh pastries, followed by coffee. The food was delicious and imaginatively prepared but there was too much. I deviated from my “no meat” rule because of the fixed menu served here.

We are now on the road from Mandawa to Jaipur. So far the road has been too bumpy to write but now we have made it onto a much smoother road.

Back at Mandawa Castle, breakfast, like dinner, had been an over-abundant mixture of western and Indian food. We had a banana and a papaya, various kinds of western bread, eggs cooked to order, porridge and tea.

After breakfast we explored the ground of the hotel and then checked out and met our driver to start our journey to Jaipur.

Shortly after we left Mandawa we entered a similar town called Mokunjur. There we stopped and a local boy gave us a tour of the “Haveli,” which are mansions from the era of the British Raj that are now in various states of disrepair. Each has a series of interesting paintings that depict everything from Hindu gods and religious stories to pictures of British railway trains.

Our guide took us into one of the Havelis. There is a front courtyard, traditionally for men, and a back courtyard, originally for women.

The most interesting part of the tour for me was a visit to a temple of Krishna, who is an avatar, or human incarnation of Vishnu, the Sustainer, one of the three main Hindu gods. (The others are Brahma, the creator, and Shiva, the destroyer.) Every household worships one of these three. Ruchi, for example worships Shiva. It may seem strange to worship a god of destruction, But destruction is part of the cycle of existence. Thus it is that death must follow life for all of us, and indeed all life. So too, astronomers tell us that new stars are born out of the remains of previously destroyed stars. And indeed, Hinduism teaches that our universe was created following the destruction of the previous one. And who's to say that the Big Bang wasn’t preceded by another universe, perhaps vastly different from, or perhaps identical to ours?

If we may return from the cosmology of the universe to the Hindu temple in Mokunuur, there was a worship service going on at the time. There were two men sitting in front and a group of about 10 worshipers, all women, sitting on the floor listening to one of the men who was, our guide tells us, reciting in Sanskrit. I think that means that the women in attendance probably didn’t understand what he was saying.

There were several women who shyly turned and stole glances at us. One woman was braver and turned to look at us several times. When I smiled and nodded at her she smiled broadly back.

The street we had taken to the temple was the market street. I guess there are markets in front of churches and temples almost everywhere in the world.

The street was lined with vegetable stands or vegetables were just laid out on cloths on the street. Behind were shops inside the first floor of one- and two-story buildings. The street was crowded with sellers, buyers, and loafers. There were also scrawny dogs, donkeys, and cows running about.

Coming back from the temple we took a side, residential street. The difference was striking: no hawkers, no throngs of people. It was quiet and mostly deserted.

Now, some two hours later we are back on the road. We have mostly been driving through countryside, mostly under cultivation.

At the moment we are driving through a relatively large town, Jomu. There are men and women everywhere. The women are as colorful in their bright saris, as the men are dull in their dark-colored western clothes.

Now we’re heading out of town. There are less buildings and people.

We are behind a bus but I'm sure we will pass soon.

Here are several camels resting in a field by the side of the road. In the next yard are a like number of cows. The camels are beasts of burden, but the cows are holy and do pretty much whatever they want. We saw one cow a while ago with its front half in the doorway of a shop. What was it doing? Cooling off? Satisfying its curiosity? Buying a Pepsi?

Now we slalom through a series of traffic barriers—the only effective speed control (along with frequent speed bumps) in a land that seems to be devoid of traffic cops.

Here's a motorcycle with two riders—a man in front, wearing a helmet, and a woman in sari riding side-saddle on the back. Lots of men (but not all) seem to wear helmets when riding a motorcycle or scooter, but few women do.

Now we’re on a four-lane divided road. A truck is ahead of us passing a bus, but it seems to barely have the power to overtake the bus. Our driver leans on the horn but the truck doesn’t pull over even after it is past the bus. Our driver's long horn blast would be grounds for road rage in the U.S., but here neither driver seems perturbed. The passenger in the truck passively motions us around.

Now we stop to refuel. We discover that our Toyota is a diesel vehicle.

Our driver informs us that we are on the outskirts of Jaipur—the new part of the city. It is now 12:50. For the next five minutes I'm going to count types of vehicles.

Passenger vans: 3

3-wheel jitneys: 2

Motorcycles: 18

Construction crane: 1

Bicycles: 3

Cars: 4

Small truck: 1

Tricycle (carrying freight): 1

There is also one stop light—the first we have seen since Delhi.

We ate lunch at the Indiana Restaurant in Jaipur. They even have a flag from the U.S. state of Indiana. The name, “Indiana,” is a cute pun with a hidden meaning: The owner of the restaurant graduated from Purdue University in—you guessed it—the state of Indiana.

My wife and I shared an order of “Paneer a la Indiana,” served in a masala (mixed spice sauce) with coconut, vanilla, and pineapple added.

After lunch we went to a chemist to get some cold medicine for me.

Then we went to the hotel. I was expecting something like the one we had in Delhi (which hadn’t been that nice), but this one is quite nice.

The driver offered to take us shopping this afternoon, but I've decided to stay in the room and rest.

We went to the coffee shop for dinner, but were turned away because it was reserved for some tour group.

We were directed to the Highz, so called because it’s on the top floor. The restaurant was posh and elegant and could easily rival any eating establishment in Manhattan. The food was quite good although the spiciest I've experienced so far. The service was very attentive. There was live music, similar to the night before.

I'm feeling better from my cold. I tried to get the driver to switch today's activities with tomorrow's but I don’t think he understood me. Besides he informed us that a guide has been arranged and was already waiting. So we decided to stick to our original itinerary and thus we headed for the town of Ajmer.

It took us a while to wend our way out of Jaipur, which is a large city, the capital of the state of Rajasthan. Once we left town we were on a six-lane expressway for a while—the smoothest, fastest road we’ve been on in India. Eventually, however the road narrowed to two lanes and then one.

Once we arrived in Ajmer we parked at the side of a busy market street. Our driver told us to wait for the guide to show up. The car was immediately surrounded by a hoard of beggars and hawkers most of the latter were selling hats, as covering one's head is required of both men and women when entering the mosque we plan to visit.

Once the guide arrived, I confirmed that I really need a hat, so I bought one for five rupees (about ten cents). They were also selling women's scarves but my wife already had one. Once my wife donned her scarf and I my hat, the hawkers went away, but not the beggars, who followed us as we began walking through the narrow winding streets to the mosque. The streets were noisy with radios blaring from shops and people talking on the streets. We constantly had to dodge donkeys, cows, and motorcycles. The sights and sounds were so foreign that I felt like I was in another world and in a very real sense I was.

The beggars followed us the whole way, grasping our arms and talking to us non-stop.

Once we reached the entrance to the mosque the beggars fell away. This is in contrast where there is plenty of commerce outside the temple grounds, but once inside, there is none.

We climbed the steps and removed our shoes. We went inside to a courtyard that looked pretty much like the outside, complete with shops and makeshift stalls selling food, souvenirs, etc. We climbed some further steps and entered into the main section of the mosque, a small room with a rail separating the public from the area where the imans stood. The public part was jammed with people. It was difficult to move. We made our way to the railing, bowed and a green cloth was then thrown over my head and I received a prayer. After that the guide expected us to go around the side of the room, but it was very crowded and although I might have braved it, I knew my wife was uncomfortable, so I asked that we go outside.

We made out way back out. The guide gave me five rupees to pay the shoe watcher.

We returned to our car and drove to Pushkar. This was only a short distance from Ajmir, but a quite spectacular ride. Pushkar is located in the mountains, and the road winds its way up into those mountains.

The area is considered a desert although there are some green plants dotted about the landscape. The combination of desert and mountains makes for a stark beauty.

On the way to the top we passed a Hindu temple dedicated to the god, Hanuman. The area surrounding the temple is swarming with monkeys. Ruchi later told me that this is because of the food used in offerings at the temple, which the monkeys find enticing.

We continued to climb and soon reached Pushkar. Again we found narrow crowded market streets. We stopped the car and began to walk to the temple. Our guide told us that the temple would ask for money. He said we could give or not as we wished, but he said he couldn’t say anything in front of the priests. In front of them he had to say “yes”.

We walked the streets toward the temple of Brahma, the Creator—one of the three major gods of Hinduism. The streets here are pretty much devoid of motor traffic, making them much quieter. There are a few beggars and no hawkers.

We entered the temple and bought an offering of flowers. We were led to the main temple building. There we were told to give half the flowers.

Brahma had two wives. When he took his second wife it angered his first wife who put a curse on him that his images and temples would be few. This temple we are at is one of those few. But if one looks to the top of the highest surrounding mountain one sees a temple to Brahma's first wife. I guess that shows who wears the pants in this Indian pantheon—and in Indian households too, I suspect.

We were then led down to a lake. This lake is completely surrounded by buildings but at certain points there are gates. It was to one such gate that our guide took us. This consisted of a covered broad set of steps that led down to the lake. I was given over to a priest and my wife to another. She was not allowed to proceed down the steps very far. The priest guiding me asked me some questions and then said a mantra, in Sanskrit I presume, and then in English, asking for health, prosperity, etc. He had a pan and had me put my remaining flowers into it. It already contained some salt and a red-colored powder and some grains of rice. He mixed some holy water with the red powder and used his thumb to apply some to my forehead.

Next he bade me go down to the lake and throw the remaining contents of the bowl into the water. When I climbed back the few steps to where he was sitting he asked me if my parents were alive. I said they were not. He showed me how to pray to them. He had me cup my hands and he poured holy water into them. As I poured the water back into the bowl I called my father's name. He said I was offering the water to my father to drink. In return my father would watch over me and my family. I repeated this two more times then did the same three times with my mother's name. I felt strange calling them by their names—I had never addressed them as anything other than “mom” and “dad.”

The priest asked my daughters’ names and then had me repeat a mantra blessing them. Then he asked me to give a donation to feed the poor. He suggested US$1,000. I told him I was only carrying 500 rupees (about $10). Eventually he settled for that but he didn’t seem very happy. In truth, I would have given more but it really was all I was carrying. But no way would I have given $1,000.

After that the priest took me to an office where he showed us photographs of food being prepared and served to the poor.

Then we left the temple area and our guide and went to a very fancy hotel for lunch. It was rather late and so we were the only customers in the restaurant. Ruchi called while we were waiting for our order. My voice echoed through the restaurant as I spoke to her, even though I was trying to keep my voice down.

After lunch we drove about two hours back to Jaipur.

I've decided to do without my cold medication today to see if my cold symptoms return.

Today we will sight-see in and around Jaipur.

First we drove to the Amber Palace. Along the way we stopped to look at the Wind Palace. This is really just a facade of a building, not unlike a Hollywood set. Its purpose was to provide a place for ladies of court to sit and look down on the passing crowds from behind a window screen so that they themselves would not be seen. Since the building is essentially a false front we contented ourselves with taking a photo of the front.

There were also two snake charmers there so I took their picture as well.

We then proceeded out of Jaipur and a short distance to the Amber Palace. This palace is the former residence of the local king. It is well protected, being on a hill in a valley surrounded by even higher hills. There are watchtowers on each of these higher hills.

To get from the valley up to the palace, we went by elephant.

At the top, we were guided around the palace. There is an outer courtyard for visitors, and lesser-ranking court officials. The inner portion contains the quarters for the king and his wives and courtesans. The king and each of his wives had a separate apartment each consisting of an outer semi-open living space, an inner sleeping space, and an indoor toilet with a drainage system to carry the sewage away. The living spaces faced the inner courtyard. The wives’ apartments were on the ground floor. The king had 12 wives and so there were three apartments on each of the four sides of the courtyard. The king's apartment was on the second floor (or should I follow British/Indian convention and call the floor above the ground floor the “first floor”?) The king had over 100 concubines and they lived also on the second floor. We didn’t see their quarters but they must have been much more crowded than those of the wives.

The central space of the inner courtyard was divided into two sections. One provided a place for the women to entertain themselves and the other contained a formal garden.

Adjacent to the residence area was another building where court was held. This building has two large domes which actually conceal water tanks. Water from these tanks traveled along pipes into the main room where they dripped down onto curtains. The breeze blowing through the curtains kept the room cool. Thus, even though this palace was built hundreds of years ago it had air conditioning as well as indoor plumbing.

When we completed our exploration of the Amber Palace we drove back to Jaipur.

On the way back we stopped at the “Textile and Carpet Merchant” where they showed us how they make wood-block printed textiles and weave carpets.

Then we were shown into an elegant, well-lit carpet showroom were various carpets were shown to us. I love oriental carpets so I ended up buying one of the smaller cheaper ones. I nevertheless felt someone uncomfortable and put-upon to be taken to such a place and given a hard sell.

Then we returned to our hotel where we ate lunch.

After lunch we went to see some ancient astronomical instruments including the world’s largest sundial which can read the correct time, accurate to two seconds.

They also had several smaller sundials, as well as a collection of devices, one for each sign of the zodiac, which tell where in the sky that constellation is at the moment. There was also a large sky map. In order to create these latter two, the builders would have had to make accurate measurements of the location of various heavenly bodies. There was an instrument here to do just that: one could line up any object in the sky and read out its elevation and azimuth at that moment in time.

With instruments such as these, the Indians were able to determine that the earth travels around the sun some 1200 years before Copernicus made the same discovery in Europe.

Next we went to the City Palace, the residence of the Maharaja of Rajasthan. (“Maharaja” is a Hindi word, but the term was invented by the British who added a higher order of governmental organization than the traditional local tribal rulers or “rajas”. The Maharaja of Rajasthan lost his power with the coming of the Indian Republic in the mid 20th Century, but he did not lose his wealth and he still occupies a portion of the palace.

The remainder of the City Palace has been given over to a museum, displaying various historical items such as royal clothing, weapons, conveyances, carpets, and miniature paintings.

We next went to a jewelry emporium where we were shown methods of polishing precious and semiprecious stones. As at the carpet emporium we were shown into a swank showroom with hundreds of expensive jewelry items for sale. Since neither my wife nor I wear jewelry we bought nothing.

Now we are back at our hotel waiting for dinner.

I’ve just come back from dinner. We again went up to the restaurant at the top of the hotel. Tonight we got a window table. We saw fireworks several times. The fireworks signify someone’s wedding celebration. It is an indication that this is the “wedding season”—the time of year which is most auspicious for getting married. It is also a reminder that we will soon be transitioning from our role as tourists to that of wedding guests and also house guests. I am so much looking forward to both of these, but somewhat nervous too. Will we get lost in the crowd? Will we know what we are supposed to do, and when? Also, I hope to be a properly polite guest but am not sure I’ll know correct behavior. I already know for example that it is impolite to give or accept anything with one’s left hand, but that will be difficult for me because I am left handed. But if Ruchi’s family is as gracious as she is, I’m sure it will be fine.

Today we head for Agra. The closer we get to meeting with Ruchi and her family, the more excited I feel. I think of Agra as “her” city even though she and her parents live an hour further in Firozabad. Still we will first meet with her in Agra at her grandmother’s house. And her wedding ceremony itself will be in Agra as well.

I am reading a book on Eastern Religion and Philosophy. I have just finished the section on Hinduism. It has given me a better understanding or at least appreciation of the complexity of the Hindu pantheon. I certainly can’t claim to know all of the gods of Hinduism—there are, after all, 330,000,000 of them or so it is written.

As for Hindu practice and beliefs, there seems to be something for everyone. There is monotheism. There is polytheism—paradoxical though that may seem. There is animal worship, idol worship, ancestor worship.

I have seen two particular examples of public practice. There was the daily service of the women worshipers. There was also the more personal ceremony that I participated in at the temple of Brahma in Pushkar. Both included prayer and other rituals for a spiritual goal. All religions seem to have a spiritual goal. If one includes such teachings as those of Buddhism, then perhaps a spiritual goal is the only thing all religions have in common. That is not to say that all religions have the same goal. The spiritual goal of Christianity is salvation—everlasting life. The spiritual goal of Hinduism is moksha, which is a breaking of the otherwise endless cycle of death and rebirth. It is often conceived as a kind of oblivion.

Most Christians believe that if one fails to achieve salvation, one will end up in the torment of hellfire. But my brother, for one, believes that failure to achieve salvation leads to oblivion. In that view the goal is eternal life and failure leads to eternal oblivion.

Hinduism (at least in my understanding of it) is completely the opposite: The goal is oblivion and failure leads to eternal life—or rather lives (through reincarnation).

India is nothing if not a deeply religions country and people. Therefore it seems appropriate for me to contemplate these things while here.

Turning from the sublime to the ridiculous (or at least mundane) I have decided to do another traffic count.

Passenger cars: 9

Motorcycles: 29

Large trucks: 14

Three-wheel jitney: 1

Tractor: 1

Small trucks: 4

Camels: 3

Busses: 6

Pedestrians: 3

Bicycles: 3

This count is a better representation of inter-city traffic. (The previous count was in the outskirts of Jaipur.) Also this time, I only counted oncoming traffic. It is possible that in my previous count I may have counted vehicles more than once—if we overtook them more than once.

We are still in Rajasthan. The road is straight and fairly smooth. It is two lanes but construction is underway to make it into a four-lane divided road. There are occasional rural villages but mostly it is open land, some under cultivation, and green; the remainder brown and rather barren, except for occasional small trees whose foliage provides a kind of green polka-dot pattern against the otherwise brown undergrowth..

I’ve decided it would be great fun to try to drive here. I think I’ve got the idea of how and when to pass. Certainly the rules are different here, but as I’ve said there is more co-operation.

Now we have come to a town and traffic is congested. There are throngs of people on either side of the road. Then as quickly as we entered the town, we are out of it.

Now we’re trying to pass a truck. Our driver keeps creeping out to look around the truck, but there is oncoming traffic which flashes its lights at our driver. Just when it’s clear the truck driver motions us to stay back and then pulls out to pass a hand cart. Then the truck pulls back and waves us around. Yes. I could do this: I could drive here. It would be fun.

Just now we come to a stretch of road where one lane is closed for repair. Our driver stops to let oncoming traffic through. Then he takes his turn. A car is coming from the opposite direction but hasn’t entered the one-lane section. He could have pulled over and waited for us but instead flashes his lights and comes ahead. It is the only time I’ve seen our driver get angry with another driver.

2:30 pm. We have just crossed from the State of Rajasthan into Utter Pradesh—usually referred to as simply UP. It seems inevitable that the road quality changes at state lines and in this case the road got much smoother—thank God. It had been pretty bumpy the last couple of hours.

We had stopped early for lunch at a place full of tour busses, mostly with French and Jewish tourists. They had some wood carvings which I have been looking for. We bought two carved elephants for our daughters.

Some time later we stopped at Fatehpur Sikri. This is the palace of a first century Mogul ruler. This palace has three courtyards, an outer courtyard for public audiences, a middle courtyard for meetings between the king and his advisors, and an inner courtyard containing residences for the king and his three wives, one of whom was Muslim, one was Hindu, and one was Christian. Each wife had a separate apartment of her own design. One was made of mirrors and silver to reflect light. One was made of gold. One was more plain but more spacious. Each cost the same amount to construct however. In this way, the king avoided jealousy among his wives over who was the king’s favorite.

The king was a Mogul and therefore a Muslim. But he himself invented his own religion that taught that there is only one God—Allah, Jehovah, Brahman, are all one and the same. As the Koran teaches, “There is no god but God.” Or the Catholic credo begins, “I believe in one God, Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth and all things visible and invisible.”

I haven’t mentioned Brahman before. It is not to be confused with “Brahmin” which is an Indian caste, nor with “Brahma” one of the three principal gods (the others being Vishnu and Shiva). Brahman is the most abstract and mysterious entity in Hinduism (although using even such a general term as “entity” is somewhat inaccurate). Unlike the principal gods, which are personified and depicted in more-or-less human form, Brahman is wholly abstract, wholly divine, the ground of being of all being and the creator of heaven and earth and all things visible and invisible. In a sense it is or at least permeates all things visible and invisible. One cannot pray to the Brahman just as one cannot point to the universe. That is why one prays to Brahma, or Vishnu, or Shiva, or one of the lesser gods or demigods—although ultimately they, too—all of them; all of us—are part of the oneness that is Brahman.

I have admiration for a king (or anyone) who can bind religions together. It is a concept that is inherent in Hinduism—there is truth in all religion—but is quite foreign and contrary to either Islam or Christianity.

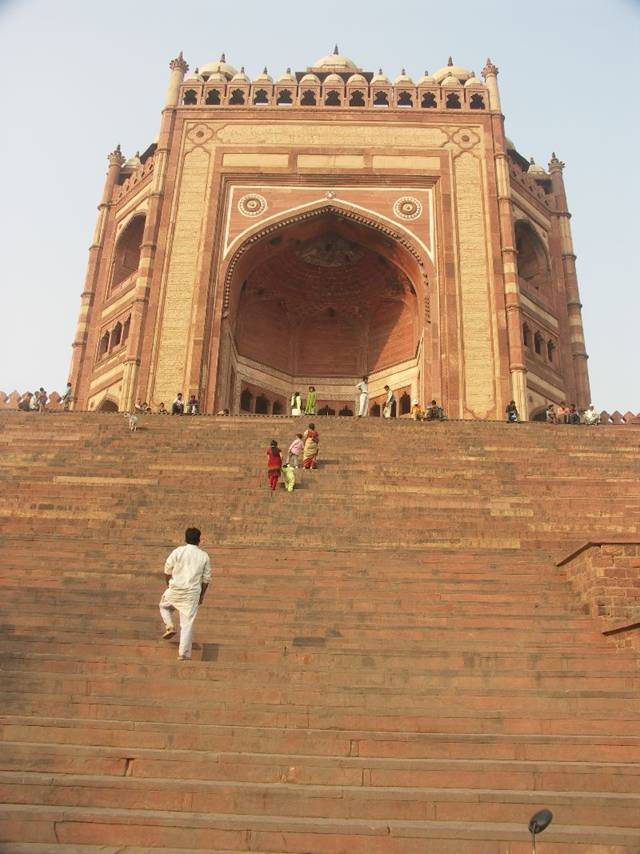

Adjacent to the palace at Fatehpur Sikri is a Moslem mosque that claims to have the largest gate in the world. I frankly doubt this claim. Whatever happened to the Great Gate of Kiev? Maybe it’s no longer standing. At any rate, this gate is quite large.

We had already been in the mosque, having entered by the more human-sized back door, so we only stopped for a moment here to take a picture.

Then we drove the rest of the way to Agra.

After checking in to our hotel, we went shopping. The places our guide took us to were all expensive and fancy—catering to tourists. I’m sure they’re intended to bring U.S. dollars into the Indian economy, and I don’t have any problem with that. But I’d just as soon my dollars went to ordinary working-class shop keepers, and just by personal taste, I’d rather see that kind of shop.

My wife bought some spices, for gifts, and for her own cooking. I bought some Indian classical-music CDs.

Then we were taken to a shop that had a room containing musical instruments, mostly sitars. A sitar player and tabla player appeared and played some music for us while we were served tea. I always enjoy live music. I consider it a special treat, and a special gift from the musicians. But, as the shop keeper remarked, “The musicians enjoy the music more than we do—for them music is their life.” I know he is right.

They played two “ragas” although there were much abbreviated, with no alat (rhythm-free section) and one with no cadence.

I bought an Indian double-reed wind instrument called a Shehnai.

The driver picked me up from the hotel and we began to drive through the still dark streets of Agra. There were two donkeys grazing across the road. We saw dogs, cows, monkeys, and a few people as we made our way through narrow, winding streets of the old section of town. We suddenly turned left into what appeared to be an alley but opened back into a road. The buildings became sparser. By now the morning light was beginning to appear. Off to the right, I saw a long passenger train go by slowly in the opposite direction.

Soon we came to a point where there was a makeshift dirt parking lot. The road continued beyond but there was an iron barrier blocking the way. The driver instructed me to walk down the road to the end. There I would find a river. The path was partially covered with trees. There was enough light to see where I was stepping, but just barely. Ahead on my right I could see a large bonfire. As I drew nearer I could see that it was an army encampment, no more than a platoon in size.

The road ended just beyond the army camp, at the bank of a river, just as the driver had said. The river bed was quite wide, but now, during the dry months, the near portion—most of the width of the river bed—was dry. There was not much more than a stream that meandered along the far side of the river bed.

And there, across the river was that which I came to see: the palace that never was a palace, an eternal symbol of one man’s love for a woman, the most beautiful building in the world: the Taj Mahal. It seemed almost luminous in the early-morning haze. Its symmetry and proportion are breathtaking in their perfection.

Probably almost everyone has seen pictures of the Taj, so I needn’t describe it here. But as with most natural or manmade wonders, seeing the Taj in pictures and seeing it in person are two entirely different experiences.

Particularly in the quiet and haze of early morning, there is something ineffable in seeing this building, looming, glowing, in front of me.

There were a few people around—a group of young Chinese women off to the left; one Indian school boy; some others further off. No one spoke to me. It was the first time I felt alone since coming to India. I relished the relative solitude.

I walked up and down the river, taking pictures or just standing and looking.

A man came by with a camel and offered to let me take a picture—for a fee, of course.

I was hoping the sun would appear through the haze but it never did and eventually I gave up and started walking back. I looked back frequently, not willing to give up my view of the Taj too soon. On the road back I came across my driver and the two of us walked the remaining distance to the car.

After breakfast we met our guide and driver and headed back to the Taj for our “official” visit.

There are no gasoline vehicles allowed near the Taj. I was told this is for protection against both terrorism, and damage caused by pollution. So we went the final distance by horse cart. I have since learned that there is an even larger circle around the Taj, within which it is not permitted to burn coal—also for the protection of the Taj from environmental damage. We were told that also for security reasons, no electronic devices are allowed, so I left my cell phone and MP3 player in the car.

At the entrance to the Taj grounds we went through a metal detector and body search. The soldier doing the search found my PDA, which I had forgotten about. The guide took it to a locker and then we were allowed to enter.

Shah Jahan was a Mogul ruler of this region in the 17th Century. He had three wives, the last of whom was his favorite. When she died suddenly, he was heartbroken. On her deathbed she made two requests of her husband. One was that he must never marry again. The other was that he do something to memorialize their love. He kept both promises. The memorial of their love was the Taj Mahal, which became her final resting place.

The shah said that his life became dark once his wife died. It is for that reason that he began planning his own burial place which should be built of black marble instead of the white marble of the Taj.

But building the Taj had practically bankrupted the kingdom so when the shah began building a second similar building, he was stopped by his son and placed under house arrest in a single room of his palace.

His daughter took pity on him and arranged a mirror to be strategically placed so that her father could at least see a reflection of the Taj.

And so, for the love of a woman, the Shah Jahan built the world’s most beautiful building and ultimately forfeited his throne. Who among us has come close to demonstrating such love?

When the shah died, he was buried next to his beloved wife inside the Taj Mahal.

Part of the beauty of the Taj is its perfect symmetry. The domes, the minarets, the adjacent sandstone buildings are all perfectly balanced one against another. There is one exception: Since the queen, for whom the Taj was built, was buried directly in the center, her husband is buried slightly to one side. I find a kind of sweet irony in this fact.

After we left the Taj, we drove to the Red Fort of Agra, built by an early Mogul emperor and occupied by several succeeding generations, including Shah Jahan. In fact most of the fort is still a military stronghold to this day. Only 25% is open to the public as an historical monument. As in past palaces, we saw expansive courtyards, large once-resplendent apartments, since plundered of their gold and jewels by subsequent dynasties or by the British. We saw the apartment where Shah Jahan was imprisoned after being deposed by his son, and from which he stole glances of the Taj.

This is what Shah Jahan might have seen from his confinement.

Next we went to a place that demonstrated the marble carving and inlay work, handed down, we were told, from the very artisans who built the Taj Mahal. Not surprisingly we were then led to a fancy showroom with marble items for sale.

Then we said goodbye to our guide and stopped for lunch. After lunch we had time to kill. I asked to be taken to a Basar (a Hindi word, the origin of the English word, bazaar). While I was expecting an exotic open-air market such as we had seen in several places in Rajasthan, in fact the place we were taken to was nothing more than a series of shops along a commercial street.

Ganesh, the god of auspicious beginnings

Shiva, the Destroyer

We then went to wait in a hotel lobby for the arrival of Ruchi’s brother, Saurabh.

This is the point of transition from tourist to house guest.

As planned, Saurabh met us in the hotel lobby and then took us first to their uncle’s tailoring shop where I was fitted for a wedding outfit. It is a long knee-length shirt with fasteners down the front. The first one they showed me was pink—a masculine color in India, but feminine in our culture, so I passed on that one.

The next one they showed me was brown, very rich in color with beautiful embroidery with sequins and beads. I also don’t want Ruchi’s family to pay for too elaborate or expensive an outfit. I am nonetheless grateful to Ruchi’s uncle for offering such finery. I asked for something simpler. After several iterations I was shown one with no sequins and some embroidery. I was happy with that one. The sleeves needed to be shortened, so I was measured for that alteration. After that, Saurabh was measured for some alterations for an Indian style suit he was having made for the wedding.

The adventure (for that is what it was) at the tailor shop was great fun for me and seemed to be for the others who watched—including our driver.

Then we drove to Ruchi’s grandmother’s house.

This was the first Indian house we will have visited. There is a central hallway running from front to back with rooms off to either side.

The house was noisy and crowded with people. We were led through the house to the back where food was being served, buffet style. Some school-aged children peeked at us shyly and then ran away giggling.

Ruchi was not here we were told. We were offered food. For the most part I had no idea what we were eating, but it was all rich in flavor, spicy, and delicious.

The children came around again, said “hello” and ran off. But they were soon back. They began talking to my wife. Soon they were all fast friends. Several adults came to talk to us as well. Some explained their relationship to Ruchi but remembering either their names or relationship are beyond my powers of recollection. Remembering names is hard enough for me in more familiar circumstances.

Eventually Ruchi made her appearance. We shook hands (which surprised me) and talked for short time. It was so good to see her again after all this time. The last time I had actually seen her face to face we barely knew each other; now I feel like she is an old and dear friend. And she is, after all, the main reason we are here.

I thought Ruchi said (although she later denied) that I had gained weight. I probably had, and maybe that's a compliment in India, but I didn’t take it as such. She had previously told me that she was worried about putting on weight, but I certainly didn’t see it. I guess I missed an opportunity to pay her a compliment.

Not long after Ruchi’s arrival, our driver called my cell phone to complain that it was getting late and he was hungry. He wanted to know when we were leaving. I told him it wasn’t up to me. I found Saraubh, Ruchi’s brother, and told him I thought our driver was getting impatient. Saraubh, responded, “I know he is; I just spoke to him.” So we agreed it was time to go. Ruchi said she would return home with us also. I objected that she had only just arrived, but she said she wanted to make sure we were ok. Saurabh gave our driver directions and then we were on our way. We were supposed to follow Saurabh's car, but immediately got separated. We found our way nonetheless. On the road our driver read me the riot act for leaving him without dinner. He said something about “These are high-class people and I am a low-class person.” I failed to understand the significance of that observation. (Later when I talked to Saurabh about it he told me he had offered our driver to come in to eat at least twice. I guess our driver was expressing to me his discomfort in accepting that invitation.)

In less than an hour of driving through the dark we arrived at Ruchi’s house a few minutes ahead of Saraubh. There was some confusion about where to take our bags—we are not actually sleeping at Ruchi’s house but at their neighbors’. This was all straightened out and we found ourselves at the home of Dr. and Mrs. Chauhan. They both spoke English and showed us to our room. In a few minutes Ruchi joined us. We discussed plans for the next morning and then bade one another good night.

Our room was quite comfortable, about the size of our own bedroom at home. It had its own private bathroom and shower.

The next morning after we arose and dressed, Mrs. Chauhan, our host, came and offered us tea and biscuits (British for “cookies”). Ruchi had told me the night before that we would be eating breakfast with her family around midmorning, so I figured the tea and biscuits would tide us over. But then Mrs. Chauhan offered us more food: mixed nuts (cashews, walnuts, and almonds) and separate bowl of almonds. Then fruit—bananas and mangos. This was the beginning of an ongoing pattern at both the Chauhan and Ruchi’s homes—we were constantly being offered food. It was all delicious although I found myself taking small portions or refusing more so as not to gain too much weight.

Whereas we took the tea and biscuits in our room, we joined the Chauhans in the central room for the remaining food. Unlike Ruchi’s grandmother's house, which was built around a central hallway, the Chauhan’s house is built around a large central room, by far the largest room in the house. It has marble floors and fluorescent lights. The other rooms, a kitchen, and three bedrooms are all directly off this central room. There is one other room, probably intended to be another bedroom, but used as a den. This home is one of four in the same building—a kind of quadruplex. Such buildings in the U.S. would probably be rentals. But the Chauhans own this building along with three brothers who occupy the other three units. Our hosts have a daughter who has the constant companionship of her cousins who live in the same building.

After we refused all further food, Mrs. Chauhan invited us to take a walk around the neighborhood. She told us she did this every morning for health reasons, although her husband (ironically a heart doctor) didn’t like to walk and seldom joined her. For us it was some welcome exercise, since we had spent the majority of the past several days sitting in a car. But more, it was a chance to see the neighborhood. We were in a “colony,” an enclosed residential neighborhood. This seems to be almost, but not quite, a gated community: there are two entry gates, but they don’t appear to be guarded.

The homes here are mostly all two-stories; they are all different. This is not a tract; these are not merchant-built homes. There are a few empty lots—potential future home sites.

When we returned to the Chauhan's house, Mrs. Chauhan showed us photographs of her own wedding and also a later anniversary party. She is proud of the pictures and I could sense the love between her and her husband—yet another arranged marrage, and more evidence that such marriages are not really different from those in our culture, even though the circumstances leading to the meeting of bride and groom, as well as the wedding ceremony itself, are certainly different. Presumably one day Ruchi will show pictures of her wedding to interested friends or family. The difference is that she may show them on a computer screen. I hope some of them will be from the pictures I will have taken.

Even though Mrs. Chauhan's wedding album is of the old-fashioned paper kind, don’t imagine that computer technology is missing from this house: Mrs. Chauhan, it turns out studies traditional Indian dance and later she showed us a recording of two of her dance recitals—recorded as MPEG files on her laptop.

Eventually we make it next door to Ruchi’s house. (I’m sure we will learn our way back and forth between the adjacent houses, but for now Saurabh escorted us.) I'm not really clear on when breakfast occurred, it seems like food was constantly being served all day. (Even though I occasionally remarked in this journal—and to Ruchi while I was there—about wanting to eat minimal portions, I have to say that the constant food was a delight: it made me feel like I was at a real feast.)

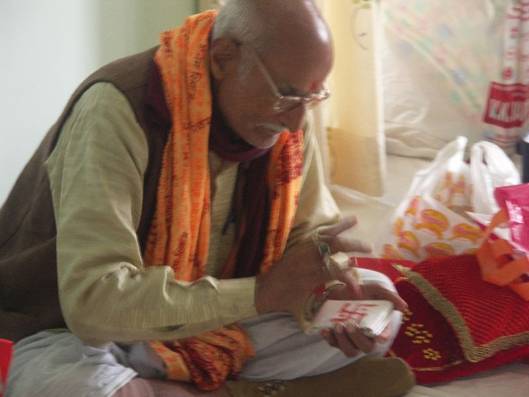

In addition to the constant food, it seems like there were various ceremonies going on all day. The first one took place in a small room on the ground floor and involved the men. I was told that the men were going to take gifts to the groom's family. The gifts (and the men) were blessed by a pundit-ji, or Hindu priest. Even though I will not be joining the group going to the groom's family, I too was blessed by the priest with red marking on my forehead and grains of rice stuck thereto.

The next ceremony involved Ruchi and her father with the same Hindu priest. This ceremony, like most of them I subsequently witnessed, consisted of the priest reciting some chant, a mantra, I presume, in Sanskrit I also presume. While he was reciting, the priest also directed the parties (Ruchi and her father in this case) to put offerings of flower petals, rice, water, money, and other things into a small silver bowl.

The pundit-ji

Ruchi (front right), her father (in white on the left)

During and between these ceremonies the married women in the family (the age of Ruchi’s mother and thus presumably Ruchi’s aunts) were engaged in singing to the accompaniment of a dholak, a double-ended drum, played by one or another of the women. I assumed these songs have some sort of religious meaning, but Ruchi later told me that at least some of them have humorous lyrics, for example, making fun of her soon-to-be in-laws.

The highlight of the afternoon was the painting of women's hands with henna. There were three artists—all young women. It seems that one of them is the senior and she first did Ruchi’s mother and then Ruchi herself. She worked as if she is making up the pattern as she goes along. The other two henna artists work from a book of designs and paint the hands of other women present. They offered to paint my hands but it never happened—probably just as well since I'm not a woman.

Ruchi’s mother

Once Ruchi started the ordeal of having her hands—and feet—painted, she invited me to sit with her which I gladly did. I'm beginning to realize that Ruchi has a very expressive face—a quality I like in people. But it may not serve her well in getting through some of the more grueling aspects of the wedding. I could see her frown and grimace with the discomfort of having to sit on the floor and stay still while her hands were being painted. Eventually a pillow was produced to make her more comfortable and I helped position it. She told me that the wedding itself will be even more grueling: she described it as six hours of smiling.

The area within Ruchi’s house where the henna was being applied is a kind of central room. Ruchi’s house is a cross between the design of her grandmother's and that of her neighbors’ where we are staying. It has a central hall, but the hall opens up into something like a central room. The room is not as large as that of the house where we are staying but it is certainly taller. Ruchi’s house is two stories and this central room is the full two stories tall. The room where most of the henna application is occurring is a somewhat a separate room in that it is to one side and only one story tall, but it is also somewhat part of the central room in that it opens into the central room with no separating wall or door. The stairway to the second floor leads off the central room as does the kitchen. There are other rooms down the hall as well as upstairs. Some of them are obviously bedrooms, but for others, the purpose is difficult to discern because the furniture has been moved aside and padding put on the floor to make space for the crowds of people who continue to arrive for the wedding. Ruchi told me there would be even more people tomorrow.